Willy Van Der Meeren and the Pandemic Paradise

What is a good place to live today? Both together and alone? Both city and countryside? Under the improvised title of ‘social distancing housing’, I went in search of places to live where the architect has already built in physical – not social – distancing. Where we can still chat with neighbours but also get away from our loved ones when we need to. And without the extravagant use of space.

by Francis Carpentier (source: bozar.be): EN/ NL/ FR

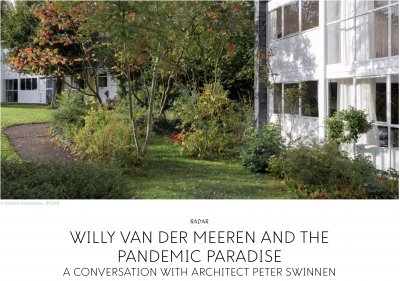

The residential project Vierwindenbinnenhof, planted among the fields of Tervuren by architects Léon Palm and Willy Van Der Meeren in 1955, is such a place. Geographically, it borders Brussels. Artistically, it is within the perimeter of BOZAR. Last summer, we let loose the Berlin collective Something Fantastic on it, as part of Artists in Architecture. Re-Activating Modern European Houses. As architects-in-residence, they created a scenario for a potential future, a manual on how to keep this protected piece of architectural landscape interesting for its occupants. And they did so using imaginative examples.

Thanks to research and publications driven by Professor Mil De Kooning (Ghent University), Van Der Meeren’s ingenious architectural poetry is still regarded as innovative today. The origin of the Tervuren project lies in Van Der Meeren’s greatest success and, also, failure: the CECA house. He joined Léon Palm in his challenge to build a prefabricated home “for the price of a Ford”. And this took place in the wake of a nascent Europe of coal and steel: the ‘Communauté européenne du charbon et de l’acier’ (CECA).

Denounced by those classical powers unable to digest this alternative “brick in the stomach”, the CECA house proved to be too far ahead of its time. It remained a case study, and not solely on the architectural but also on the social plane. Architect Peter Swinnen, who actively promoted ‘pilot projects’ as a tool during his tenure as Flemish Government Architect (2010-2015), actually moved in with his family. And even – noblesse oblige – in the house that Willy Van Der Meeren had built as his own studio and family home.

Peter, the reason I’ve called you is that I’ve been struggling with the following questions. What will this pandemic mean for the densification discussion? Where would be a good place to live at the moment?

It’s not bad here.

What was the initial intention?

In order to achieve its low price, the intention of this experiment was mass production. That failed, despite the fact that Palm and Van Der Meeren were able to gather a good 4,500 prospective applicants for a CECA home in barely a year. The eight homes in Tervuren were the result of the initiative of an interested party who turned out to have a little more capital. He owned land, and not a small plot. As principal – which I consider interesting – he pushed for an extra-large version of the home with a third bay, as he had a large family. The architects made a virtue of this necessity, and developed a cohabitation project with different CECA homes and variants. I think, without knowing all the details, that they selected from that list on the basis of profile and ‘who you know’. Not dyed-in-the-wool socialist residents but rather highly-educated people with a certain openness towards each other. That was necessary at the start, simply to get the project off the ground and realised within such a short time. Barely two years on from the exhibition of the first CECA home in Liege, the Vierwindenbinnenhof was completed and occupied.

How did the architects shape the community? How did you find them?

The basic deed was an important tool and states clearly what is and is not possible. Deviations had to be approved by Palm and Van Der Meeren initially. Invariably, references are made to the overall, let’s say, ‘master vision’ for the site. But you also soon notice – unfortunately, the community’s records are not complete in this area – that disagreements arose quite quickly. How do you deal with those community-related issues? How do you make sure that the collective interest is of equal value to the private interest?

Disagreements among the first occupants, who chose each other? Or following a change of ownership?

More a difference in sensitivity regarding the substance and interpretation of the community rules. I suspect that they were more stringent among the architects than among some of the occupants. For example, you can see it in the discussions concerning parking. Originally, the garages were an open carport in concrete. They quickly became storage spaces as the homes are relatively small, without lofts or basements. If you need to store something, even today, you will use those spaces. This was soon commented upon in those reports: “Can you please ensure that the open garages are not full of rubbish?” The tone is quite direct in those reports. Which could also demonstrate that there was a lot of trust among the various occupants.

And today?

For the last two years we have been the spatial administrators of the Vierwindenbinnenhof and are working gradually towards a respectful upgrade. There are still several different versions of day-to-day use today. I think we are noted as the residents who are closest to the original concept. I find the concept a generous one, with plenty of room for manoeuvre. To be honest, I personally don’t see it as a restriction. On the other hand, we compensate for that by dealing with the things under discussion in a hands-on way. For example, we’ve just laid a green roof on top of the garages so that our neighbour can place her beehives there. Things like that are not attacks on the initial idea but necessary changes that keep the landscape productive. Soon we will be resuming the restoration of the garage space, and we’ll restore the gardens to a freer arrangement.

How is life at the Vierwindenbinnenhof during this coronavirus crisis? What impact does it have on community life?

It’s no different to usual, really. There is probably a greater sense of confinement felt in the smaller homes. When we bump into each other on the path we do unfortunately take a slight detour now. But that’s out of mutual care. Respect for each other has certainly not deteriorated. Actually, the opposite is true. As we don’t live on a traditional street, a neighbour took the initiative of blowing a horn to summon everyone at eight o’clock. It didn’t quite work the first time, and we thought “what on earth is that?” Now, our four-year-old daughter lets us know when it’s almost eight and she’s ready and waiting with a range of instruments.

And do you talk to each other then?

It’s a moment to informally check: “Is everyone still okay?” Some prefer not to leave their houses. We then go up to the houses to ask if there is anything we can do to help, especially among the older residents. Of course, I preferred things the way they were. Normally we’d give each other a kiss or a hug. That conviviality has certainly not deteriorated but it is different now, of course.

But it was also ahead of its time in this way too.

Palm and Van Der Meeren didn’t possess a crystal ball, but the fact that their concept can also withstand a pandemic like this so well is impressive. It functions the way it should function. Very generous. Very considerate. The idea of an ‘enclosure’ but without really being enclosed. The degrees of privacy are well thought-out. And what’s also not unimportant is the mature character of the landscape, now 65 years old with beautiful trees and plenty of flowers.

What can collective housing projects learn from a place like this?

Let people make their space their own. Although this means a certain degree of freedom, the private element implies care. All too often, social housing leads to sterile neighbourhoods dictated from above, where no one feels a personal engagement or likes to live. Densification should not be a dogma, and must always be a choice. It works best if it is moderated and not market-oriented. That’s the big mistake that’s made today. You can’t accuse me of being romantic for wanting to live in ‘the country’. I still maintain that we live in an urban region, despite the fields around us. Urban means mixed. This is an ecologically and socially productive landscape in which the urban ingredients are still present. The only major ‘but’ is that public transport has been reduced by half over the last three years. If you miss the bus, you’ve had it for the rest of the day. I find it incomprehensible and irresponsible that a government should blindly cut back on public services in such core areas. This is prime territory in Belgium and Europe and should be easily accessible. End of.

source: bozar.be